Texas Tech Researchers Played Important Roles in Covid-19 Testing

In March of 2020, it seemed a lot of the world slowed down as COVID-19 shutdowns began. But for some Texas Tech University researchers, their work sped up.

Personnel from across Texas Tech jumped to respond to a need as the new disease began its rampage through the world. Some started researching possible vaccines. Others developed new ways to test for the virus. And still others donated supplies and even helped to create materials needed for polymerase chain reaction tests, or PCR tests.

Researchers saw a need, and they responded.

Texas Tech Called to Action Even Before Shutdown

Before a lot of people were even aware of COVID-19, and before the world began shutting down, Steve Presley and his team were concerned.

Presley is a professor of environmental toxicology and director of The Institute of Environmental and Human Health, or TIEHH. Presley's lab group runs a Laboratory Response Network, or a reference laboratory, for the Centers for Disease Control. There are 10 LRNs in Texas and about 140 worldwide.

In January 2020, he and his team met with other leaders of LRNs in Texas for an annual conference.

“One of the people was talking about this weird virus in China,” Presley said. It was enough to catch their ears. He said not long after returning, Cynthia Reinoso Webb, the lab manager and biothreat coordinator, suggested they start preparing.

Prior to COVID-19, Presley said, the LRN was a high-complexity, low-throughput laboratory. That means their capacity for testing was 85 samples per day, if everyone in the lab was present and working.

“We went from that, COVID happened, to where we were doing, conservatively, more than 400 samples a day. It was a significant leap in equipment, manpower, everything. But we were the first lab in Texas to test for COVID-19,” Presley said.

During the Omicron variant surge in the winter of 2021-22, he said the lab sometimes was testing more than 900 samples per day.

Some of the LRNs in Texas were never able to ramp up their testing capacity. Presley said they could have kept their lab's capacity to only 85 samples per day.

“We could have said that, but…” he said, pausing for a long while. “I couldn't have said that, morally. It wasn't a choice. It's bigger than the pandemic. It's something that needs done. You've got to step up and do it.”

“If you have the ability, you have the responsibility.”

He said one of his team members has a saying that he believes is fitting: “If you have the ability, you have the responsibility.”

But in order for Presley to even do the testing, he had to get extra equipment from the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, and he really needed a way to transport samples in what is called viral transport media, or VTM.

Making the VTM

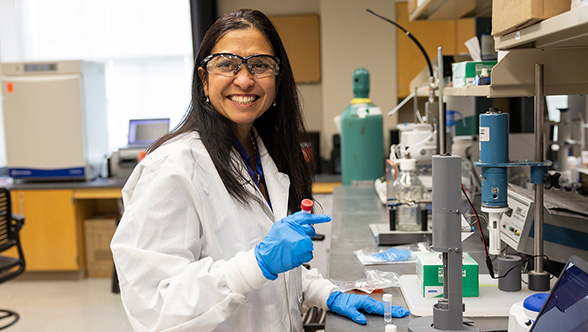

Harvinder Singh Gill is a professor and Whitacre Endowed Chair of Science and Engineering in the Department of Chemical Engineering with the Whitacre College of Engineering at Texas Tech. Presley asked if Gill's lab had the expertise to make the viral transport media, or VTM, and Gill said they just needed a recipe. Once the CDC published that recipe, his lab began cranking out thousands and thousands of units of VTM under the direction of post-doctoral associate Gaurav Joshi.

“They offered to pay us, and we said, we don't need anything,” Gill said. His lab has created the VTMs for Covid testing, requiring only reimbursement for the supplies. He said they have made almost 200,000 tubes of VTM for Presley and for the state of Texas.

“This is not something to make profit off of. People are miserable,” Gill said.

“He gets it,” Presley said of Gill. “He understands the importance of being able and willing to respond and to make it work and ignore all of the noise and chatter. Harvinder's a good guy.”

This is not Gill and Presley's only contributions in the age of the pandemic.

Together, they have a grant from the National Institutes of Health to create a universal flu vaccine. With their work in that area, Gill said they worked to create a possible COVID-19 vaccine, one that would be responsive even as the virus mutates.

“We formulated a candidate vaccine which we thought would be effective,” Gill said.

However, before the virus had mutated into Delta or Omicron or any of the other variants, scientists said they did not believe it would do so. Gill's grant proposal to the NIH was turned down.

“The reviewers basically said, you are on the wrong path because Coronavirus doesn't change. Eventually, of course, they were proven wrong, and we had a whole slew of different mutations,” Gill said.

Designing a New Test

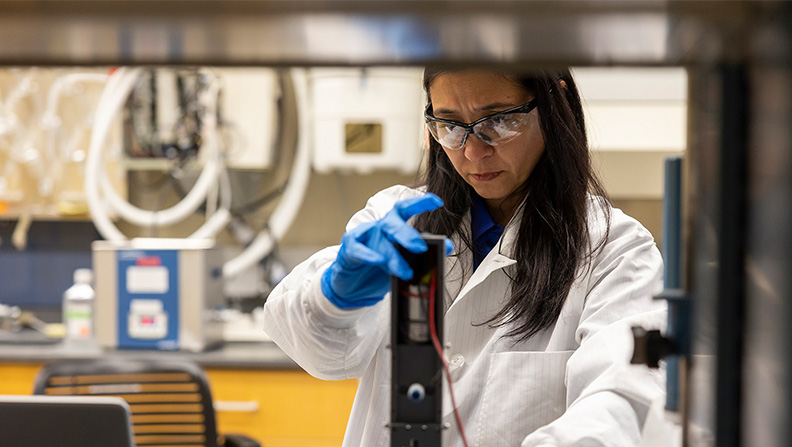

Gerri Botte is a professor and Whitacre Department Chair of the Department of Chemical Engineering. When the pandemic began during the spring semester of 2020, Botte was working on sensors to detect microbials and an equalizer for pathogens in wastewater and food.

As most research came to a standstill at Texas Tech, Botte thought about her existing research and wondered if it could be adapted to find a way to more easily test for COVID-19.

“I told my graduate students, there might be something that we could do with what we already have built, if we make changes and modifications in the chemistry or in the device, and we could use it for COVID-19,” Botte said. “Obviously, it was very early. Nobody knew what to do, where to get viral samples, etc.”

Botte and her student, Ashwin Ramanujam, coordinated with Sharilyn Almodovar, an assistant professor of immunology and molecular microbiology at the Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center. Almodovar's laboratory had access to the safety measures required to test viruses and proteins of the COVID-19 virus early during the pandemic.

Botte's device can detect the coronavirus in saliva, but she is also working on a patent that would identify the virus in the air. Texas Tech researchers were one of just 111 who were issued a patent by July 2021 from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office under an expedited process to fight COVID-19.

A more traditional way to test for a virus involves a Polymerase Chain Reaction test, also known as a PCR test, which are used to directly screen for the presence of viral RNA, which are detectable in the body before antibodies form or symptoms of the disease are present. Presley called the PCR test the “gold standard” for testing, but each of those tests requires lab analysis, which takes time.

Botte's method involves applying an electrical signal into a device and passing it through the device via a chemical solution. The COVID-19 proteins that pass through this electric field respond to the electrical signal, allowing the tester to determine if the virus is present.

The device that Botte developed was used in 2021 in the J.T. & Margaret Talkington College of Visual & Performing Arts among student performers in dance, choir, and musical ensembles. The college needed a way to screen as many as 150 students on a weekly basis to prevent an outbreak, according to Genevieve Durham DeCesaro, interim dean of the college in 2021.

“We would not have been able to continue in engaging in our in-person production performance activities,” Durham DeCesaro said of the testing that Botte's device provided within minutes. “We counted on the arts being able to be in-person, and so the significance of our institution having a solution for us cannot be understated.

“There was not another institution in the state of Texas using this specific model.”

Durham DeCesaro said after an entire fall term of live events with very limited outbreaks, it was partially due to Botte's testing device.

“Being able to capitalize on the innovations made by our colleagues over in engineering and use those innovations as viral mitigation measures was really an opportunity that we could not turn down,” Durham DeCesaro said.

Responsive Research

Texas Tech researchers are conducting research that is responsive to the needs of the West Texas region, the state, the nation, and the world. A century later, their effort to contribute in a challenging time continues to fulfill the mandate of Senate Bill 103 in 1923, which formed the Texas Technological College to establish a college in West Texas.