100 Impactful Moments

Volunteerism & Service

Join Red Raiders around the world as we strive for one million hours of volunteerism and service.

Learn MoreContact Us

Do you have a question about our celebration? If so, send us an email

Texas Tech Centennial

100 Impactful Moments

Traditions

History

Student Life

Athletics

Academics & Research

Facilities

Trailblazers

Philanthropy

Regional & International

Alumni

The System

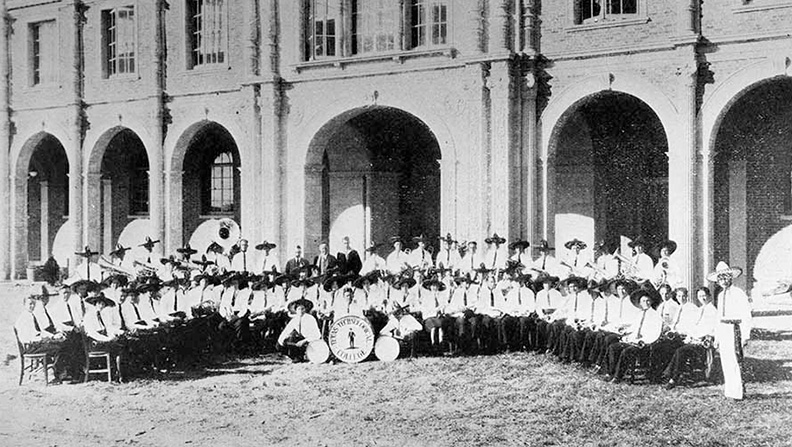

1926: Tech Band Takes Historic Trip to Become Goin' Band from Raiderland

In 1926, beloved American humorist helped Tech’s then-called Matador Band become the first college marching band to travel to an away game.

According to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram:

“Will Rogers wants Fort Worth to see a ‘real West Texas band’ and hear some real West Texas music. That’s the reason he gave $200 to help bring the 80-piece band of Texas Technological College to Fort Worth for the game with TCU Saturday.”

The Matador Band became the Goin’ Band from Raiderland.

For almost a century, the Goin’ Band has created:

- A family.

- A tradition of hard work, excellence and fun.

- Band 1 and Band 2…and Band 3.

- The foot-and-a-half.

- Service organizations.

- A lot of music and marching.

In the Beginning…

In 1925, the Matador Band performed at Texas Technological College’s first football game in 1925 with about two-dozen members, under direction of W.H. Waghorne.

The next year, Harry Lemaire arrived in Lubbock to lead the marching band and take it on that Fort Worth trip.

Lemaire was already 64 years old. He’d been a bandmaster under Theodore Roosevelt during the Spanish-American War and knew famed American band director John Philip Sousa. During his eight years at Tech:

- First band to have its halftime show on radio on WBAP in Dallas/Fort Worth – long before the phrase Metroplex was born.

- Because Tech’s teams were the Matadors, Lemaire had band members wear Spanish look with a Gaucho hat (like now) and chaps.

‘Father of Bands’ Lands in Lubbock

D.O. “Prof” Wiley was the last Tech band director born in the 1800s and the first of three men who over 68 years transformed the Goin’ Band from its early years to a source of pride for Red Raiders.

Wiley was known as the Father of Bands in Texas, developing the popular Cowboy Band at Hardin-Simmons University before coming to Tech, where he expanded the band to more than 200 members.

“He really put the Tech band on the map,” said Keith Bearden, who later played in the Goin’ Band and became the first alum to direct it in 1981.

During Wiley’s time in Lubbock:

- The Tau Beta Sigma band sorority was founded at Tech in the 1930s and the first Texas chapter of Kappa Kappa Psi for men was formed at Tech. Even though Tau Beta Sigma was the first chapter, Wiley called Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State University) to offer them the chance to have the alpha chapter because they’d started Kappa Kappa Psi. When Sarah McKoin came to Tech to be director of bands, she found out how serious the two groups are about service. “Within five minutes of coming here, there was a group of kids who gave me a gift basket and asked if they could help me move into my house. I gave them the keys to my house and said, ‘I’ll meet you there,’” she said, laughing at the memory of handing people she’d barely met her house keys.

- Wiley started Phi Beta Mu, the international bandmasters’ fraternity and years later Bearden served three years as the group’s president.

- Few women were in the Goin’ Band in its early years, but during World War II, the band was almost all women when men were fighting the war. “Women really kept the band going during those days,” said Bearden.

The Man from Nebraska

Nebraskan Dean Killion brought a Big 10 Conference look and feel to the band, eventually expanding it to more than 400 members.

He abandoned the Spanish-looking uniforms, replacing them a garrison-style hat with plume, military-looking coat with breastplate – a look more like Big 10 Conference bands.

Killion started the Court Jesters band for Red Raider basketball games. Dick Tolley came to Tech the same year as Killion to teach brass and helped direct the Goin’ Band.

Band 1 and Band 2

“We started with 120. By the second year, we enrolled 205,” said Tolley. “Dean decided to divide the band into two units – Band 1 and Band 2 with the percussion session in the middle.” The idea was to split the band in half, so the audience heard the same performance. It created a stereophonic effect. Killion also created a hilarious rivalry.

Jay Sedberry, president of the Goin’ Band Association – a group of band alumni who support the band – was an alto saxophone player in Band 2.

Chris Brewer, treasurer of the same group, was a Band 1 trombone player.

“Band 1 and Band 2 are identical. But everyone knows Band 1 is better than band two,” said Brewer.

Sedberry disagreed.

“Band 2 is better than you because Band 1 has no fun,” he said while the two discussed their time in the Goin’ Band.

Sedberry went on to fill many roles in the Ropes Independent School District southwest of Lubbock, including assistant band director.

A former Band 1 tuba player worked with him for a while and they’d jab at each other about the Band 1 and 2 rivalry.

“I pretty much convinced the majority of the Ropes band that Band 2 is better,” he said.

On the Goin’ Band’s alumni website, bios of Board of Directors point out which band they were in.

“Speed of light is faster than speed of sound.”

As the band grew, Tolley was one of three directors helping Killion conduct.

“Speed of light is so much faster than speed of sound. If the people on my side just listened, they can be late. We wore white gloves,” Tolley said, so the students could easily see their hands.

Tolley kept an eye on Killion. Even if Killion slowed down because he got tripped up, Tolley matched his tempo.

Percussion, color guard and auxiliaries were unofficially Band 3. They didn’t march, so during rehearsals, they had fun while Tolley was conducting on a ladder.

“These guys would tie my shoelaces together, roll my socks down, roll up my pants while I was up there helpless. I was sympathetic to their plight – they had time on their hands.”

“These guys would tie my shoelaces together, roll my socks down, roll up my pants while I was up there helpless,” he said. “I was sympathetic to their plight – they had time on their hands.”

Band 3 also call themselves ZIT – Zeta Iota Tau – a mock fraternity.

Killion was a Salesman

Killion grew the band by recruiting on campus.

“He would stand out in the hallway in administration. In those days, we only had 8,000 students. All the students had to go through Administration during registration. He was out in the hallway confronting kids – but he had a genial way about it,” said Tolley.

Killion would get a student talking, finding out if they were in marching in high school.

“If they did, he’d ask, ‘Are you going to be in the band?’ If the kid would say, “No, I don’t have time.’ The he’d say, ‘Well, let me talk to you.’ Kids couldn’t resist him. The band grew exponentially,” said Tolley. About 25 percent are music majors.

How Music for Masked Rider’s Run was Written

Tech’s head cheerleader went to Killion asking if there was a way to tie the band, cheerleaders and the student body all together. Killion told him to visit Tolley.

“He’s from Illinois and they had terrific tradition up there. I’m sure he’s got an idea,” Killion told the cheerleader about Tolley.

They came up with the idea of a fanfare for when the Masked Rider led the football team on the field and ran around the stadium.

“I took the theme from one of our most popular marches. It caught on. I really get a kick that they’re still using it,” Tolley said.

Years later, Tolley saw his youngest granddaughter play the enduring music on trumpet he wrote years before.

Foot-and-a-Half

Bearden came to Tech to play for Killion.

“He was my role model. I wanted to be like Dean Killion,” he said.

Killion created the foot-and-a-half.

“People are wandering around and he’d say get into your foot-and-a-half. You kept one foot in place and you could roam 18 inches in any direction as long as you stayed in your foot-and-a-half,” said Bearden.

When seniors move on, they’re given a framed certificate – a foot-and-a-half “land deed” to their foot-and-a-half of the field at Jones AT&T Stadium by their work and traditions they’ve upheld, said Debbie Holt, the band’s unit coordinator, who first saw the Goin’ Band when she was five years old and her family came into Lubbock from Levelland.

Expecting Twirlers to Make Their Weight

Killion asked Tolley if they had girls in the band when he was at the University of Illinois. Tolley said no.

“Well we’re going to have girls in the band here,” Killion said.

Were there twirlers at Illinois? Killion asked again.

“Absolutely not,” Tolley answered.

“Well, we’re going to have twirlers and they’re not going to wander around, they’re going to be organized,” said Tolley, recalling what Killion said. “He spent a lot of time coaching twirling.”

Killion also weighed the twirlers, which would not be close to acceptable now.

“He’d weight them in the summer and decide what their weight was supposed to be, then every Monday, there were scales in his office. If they were overweight, they wouldn’t perform. And he told them, ‘I’m your best friend. Because up in the stands, people have binoculars. If you get fat, they’re going to talk about you. I want everyone to admire our twirlers. When you walk on campus, I want your hair fixed, I want you well dressed. People will say, ‘that is a Tech twirler,’” said Tolley, again recalling what Killion said.

Tolley’s daughter Tammy became a twirler and Killion said Tolley was in charge of weighing his daughter.

“She told me after she graduated, ‘I used to have a picture of Mr. Killion on my refrigerator. Every time I went to get a snack, I said, No – I can’t do that,’” her father said.

Replacing His Role Model

Under the Bearden’s leadership, Tech won the Sudler Trophy in 1999, what’s been called the Heisman Trophy of the college band world. It’s not a championship but awarded to a band surrounded by great tradition that’s become nationally respected.

As much as Hale Center-native Bearden revered Killion, he returned the band’s uniforms to a Spanish-influenced uniform with the Gaucho hat and cape.

“I wanted to change back to the traditional style,” said Bearden.

He kept the spats from Killion’s era and when seniors leave the band, they get to keep their spats.

Different Styles

Marching bands developed from the military and early college bands performed what’s called military style. One of the best examples is Texas A&M.

Killion’s shows were precision-drill style, said Bearden, who added corps style to the Goin’ Band.

In corps style – not to be confused with A&M’s Corps of Cadets – the marching matches the music. In precision drill, the music matches the marching, said Bearden.

“I tried to do a mixture of all styles,” said Bearden.

From Grid Sheets to Computers

Killion used grid sheets to plot out a show and Bearden used them when he took over.

“You’d mess up, throw it on the floor and at two in the morning I was knee deep in paper until you got what you wanted,” Bearden said.

The process evolved to using acetate on top of a light box and a grease pencil.

“It was very tedious and time consuming. Then along came the computer,” Bearden.

“These companies came up with software where you could place a line and say I want it to move to an arc here so you would make it 16 steps from here to there. It would chart the pathways course – these people down at the end are taking smaller steps, these in the middle are taking longer steps but everybody takes 16 counts. That’s the basic premise for all the corps-style things you see. They go from point A to point B in certain number of steps and change the look,” said Bearden.

Shows can run 50 or more pages for the students to learn and Bearden said they could learn about ten pages an hour.

Band Pranks Bearden in his Last Show

Bearden’s last show at Jones AT&T Stadium was in 2002 and without his knowledge, the band rewrote part of the show to spell out “Bearden,” not Texas Tech. ABC was told what was going to happen and had a camera on him, said Sedberry.

“Keith didn’t realize what’s going on,” said Sedberry.

Brewer said Bearden thought the show was falling apart when someone told him to look at the stadium Jumbotron so he knew about the honor.

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

Now

Joel Pagan is director of the Goin’ Band.

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” he thought when he took over.

His favorite show was a wedding show. A couple in the band had recently gotten married.

“We reached out and asked, ‘how would you like to be married again?’” he said.

The band got a preacher from a Lubbock church who officiated a wedding ceremony on the Double T on the 50-yard-line.

“The bride wore her wedding dress again. The groom came out. Raider Red walked the bride down the aisle and we played all wedding music,” said Pagan.

They played a song called “The Stripper” when the groom takes the garter off his wife’s leg. As with all songs they play, they must get permission to play the song.

“When we submitted that to our School of Music, the acting director at the time said, ‘What are you guys doing? I got a request to approve a stripper?’” Pagan said he was asked, clarifying it was a piece of music.

Goin’ Band grads who are teaching help recruit.

But when Tech is traveling, Pagan said they’ll hold an open rehearsal and get the word out for people to come watch.

Goin’ Band Association

The organization dropped alumni from its name so it could include parents of current members, Sedberry said.

“We exist to help the Goin’ Band go – scholarships, providing water, funding the bandwagon to haul equipment,” he said.

They’ve built a scholarship endowment where every dollar goes back to the band. They distribute about $11-12,000 a year to about three-dozen students.

The organization has more than 100 members and former Goin’ Band members must be a member of the association to play when the alumni band plays once a year at the stadium.

Sedberry and Brewer have lots of memories:

- Brewer was one of many who met his spouse in the band.

- Sedberry was with the band at Colorado in 2002 – which was Bearden’s last football season. They were pelted with marshmallows, water bottles and batteries. “Somebody threw a water bottle into the bell of a sousaphone,” he said.

- “There’s nothing like running out of the tunnel for pre-game. Then the Masked Rider and team run on. There’s this burst of energy. It’s amazing,” said Sedberry. Brewer added, “you get a chill down your spine when you run out of the tunnels.”

- Brewer was also one of the small team who drove the bandwagon 30-45 minutes before the game to set up. He would miss the March Over and March Back, where the band takes off from the Music Building parking lot where they practice. “They do it in such a stylistic and entertaining way. It draws a crowd and people follow them,” he said. Brewer did it once his freshman year. He wanted to do it the final game of his senior year and told the bandwagon crew they’d have to do this one without them.

‘Look at That…That’s Cool’

When McKoin came to Tech she was impressed by the connection between the band, the Tech community and beyond.

“I went to Michigan State. They have a terrific marching band and I marched there. I did my doctoral work at the University of Texas. But when I came here for my interview, one of the university buses drove by and on the side was a picture of the marching band,” she said.

“I thought, look at that…that’s cool,” she added.

Once she started working at Tech, she met people who brought up their time in the Goin’ Band.

“I saw how integrated it is into the community that’s unique from other places. The culture in phenomenal,” she said.

‘The Goin’ Band keeps going’

Holt sees a lot of band members who’ve become band directors.

“They come back and introduce their spouses to me. Then they come back and bring their children to meet me,” said Holt, whose daughter was a Goin’ Band member.

“To see how they progress from little freshmen who walked in the door scared to where they are now. They always come back – it’s a homecoming for them and it’s great to be part of that. No matter what happens in the outside world, the Goin’ Band keeps going. And it always will,” she said.

1926: Double T Created

Lucille Davis Ford kept a diary from her time at Texas Tech.

Her Jan. 7, 1926, entry: “Football boys receive scarlet and black slip-on sweaters. Very thrilling.”

A story in the school newspaper – the Toreador – had more detail about the event and the first unveiling of Texas Tech’s iconic logo.

“Coach Freeland kept the boys in suspense as to what was on the sweaters by telling of the difficulties in selecting the letter. When Captain (Windy) Nicklaus stepped forward for his sweater Coach held it so the letter could not be seen. He told of some wanting an M (for Matadors), some a T, while he thought of a P (for Plains) would be symbolic of the great surrounding country of the college. When Windy unfolded the sweater, he revealed two black outlined Ts on the front of a scarlet body.”

Coach E.Y. Freeland and his assistant, Grady Higginbotham, never said they created the Double T, but historians credit them.

Dr. David Murrah, former director of the Southwest Collection, wrote a paper on “Origin of the Double-T.”

“Just how close the Double-T came to being an ‘M’ or a ‘P’ is anybody’s guess, but Freeland probably was only ribbing his team and the audience in order to add to the drama of the occasion.”

“Just how close the Double-T came to being an ‘M’ or a ‘P’ is anybody’s guess, but Freeland probably was only ribbing his team and the audience in order to add to the drama of the occasion. The Double-T was the obvious choice for the new school and more than likely, its designer drew upon the popular block T of the Texas A&M logo. After all, Texas Tech in many minds was a West Texas A&M and its supporters at that time would have been proud to have a symbol based upon the logo of the older institution. Also, Tech’s assistant coach Higginbotham, a recent graduate of Texas A&M, probably participated in the letter design,” wrote Murrah.

Double T popularity spread when the senior class of 1931 donated the Double T bench to the campus grounds.

The class of 1938 donated the first neon Double T sign, which currently is fixed to the east side of Jones AT&T Stadium visible from University Avenue. It was reputedly the largest neon sign in existence at the time it was purchased and presented to Texas Tech.

Over the decades, the Double T’s presence grew, becoming the school’s official logo in 1963 – the same year it first appeared on the football team’s helmets. The logo also played a role in the name change from Texas Technological College to Texas Tech University a few years later.

Alumni rebelled against faculty and student votes toward naming the school Texas State or other options, not wanting to give up their Double T symbol.

In August 1987, a second neon Double T was added to the west side of the stadium, funded by Bill McMillan. It was replaced by a stained-glass Double T after renovations to the stadium’s west side in 2003.

The Double T existed in its original form until 2000, when an updated three-dimensional version was created.

Some fans advocate for the old – or classic – Double T. There’s even a Twitter account: Bring Back the Classic Double T.

Both are available on gear – so fans have their choice.

And there are lots of choices. The Double T is everywhere in Lubbock, across the Texas Tech University System and beyond on clothes, flags, face paint, buildings, holiday ornaments and more.

1930: Matador Song Written & Tech’s Other “Hits”

The Red Raider Nation – long before that phrase was used to define a sports program’s fanbase – has sung “The Matador Song,” and “Fight, Raiders, Fight” since Texas Tech’s early years.

“The Matador Song” is more powerful after a big win, when jubilant fans in a packed Jones AT&T Stadium, United Supermarkets Arena or Rip Griffin Park have their Guns Up and reach a crescendo singing “Stand on heights of victory,” finishing with “Strive for honor, ever more, long live the Matadors!”

The lyrics resonate decades later:

- Fearless Champion recently retired as the Masked Rider’s horse after nine years of thrilling fans, the horse named after another line in the “Matador Song.”

- The university recently launched a magazine called Evermore.

- The campaign started in 2014 to upgrade Athletics facilities across campus is called the Campaign for Fearless Champions.

- Strive for honor and bear our banners far and wide constantly show up in speeches by Tech officials.

What’s the genesis of Tech’s alma mater and fight song – the university’s greatest hits?

From the May 1, 1930, issue of The Toreador, Texas Technological College’s student newspaper:

Council Adopts

Song for Tech

R.C. Marshall submits tune

placed first in contest

Following agitation over a period of several years for a spirited song for Tech, the student council recently approved the entry of R.C. Marshall, transfer from Hillsboro Junior College, in a contest held for the purpose of adopting an official tune.

The words of the selection are as follows:

SONG OF THE MATADORS

Fight Matadors for Tech,

Songs of love we’ll sing to you,

Bear our banners far and wide,

Ever to be our pride,

Fearless champions always be,

Stand on heights of victory,

Strive for honor, ever more,

Long live the Matador.

Almost a year later, in the March 5, 1931, issue of the Toreador:

New Music Is

Adopted For

Matador Song

Because of controversy over the similarities of music of the Tech war song “Matadors” with that of Notre Dame’s official fight song, Harry LeMaire, Tech band director, has written new music for the song. The words have not been changed.

The article went on to say the song would be copyrighted.

The song was created as part of a Toreador contest and Marshall won $25, which today would be close to $500. Marshall was the editor of the 1931 La Ventana.

Even though Tech’s nickname changed to the Red Raiders later in the 1930s, decades later the song still pays tribute the school’s original team name. It’s also sung at commencement.

In 1936, Tech band members Carroll McMath and James Nevin adjusted the school’s fight song to update the nickname to Red Raiders. It was originally written by Vic Williams and John J. Tatgenhorst.

Fight, Raiders, Fight! Fight, Raiders, Fight!

Fight for the school we love so dearly.

You’ll hit ’em high, you'll hit ’em low.

You’ll push the ball across the goal,

Tech, Fight! Fight!

We'll praise your name, boost you to fame.

Fight for the Scarlet and Black.

You will hit ’em, you will wreck ’em.

Hit ’em, Wreck ’em, Texas Tech!

And the Victory Bells will ring out.

Bill Dean, former president and CEO of the Texas Tech Alumni Association, longtime professor and Tech grad, remembers singing the “Fight Raiders Fight!”

“Any school’s fight song is a major tradition,” Dean said. “We sang that fight song when I first came to Texas Tech in 1956 and it has been sung all the way through, and it was sung before then. It is something that is part of Texas Tech.”

“…We have one of the greatest fight songs in all of college athletics and combined with the great Goin’ Band from Raiderland, it makes it a great tradition that is enjoyed by all of our fans.”

Gerald Myers, Athletics Director emeritus loves the fight song.

“I think we have one of the greatest fight songs in all of college athletics and combined with the great Goin’ Band from Raiderland, it makes it a great tradition that is enjoyed by all of our fans,” said Myers.

Both songs are taught to new students as part of orientation.

Source:

- Preserving a legacy: The tradition behind the Texas Tech Fight Song, Texas Tech Today, Sept. 17, 2010, by Sarah Salazar

1936: Saddle Tramps Founded; High Riders Follow in 1970s

Trent Bell felt a bit nervous the first time he was part of the Saddle Tramp Bell Circle on the Jones AT&T Stadium field before a Texas Tech football game.

“You’re in front of a lot of people. It’s a tradition that’s been going on for a very long time. You don’t want to be the one to mess it up. It’s a lot of fun, though and it’s definitely exciting to pump up the crowd,” said Bell, president of the Tech spirit organization for the 2022-23 school year.

Erica Martinez was in training for High Riders – the female version of Saddle Tramps – during COVID. Sessions were on Zoom.

“My pledge trainer showed us a picture of them ringing the Victory Bells and I was like, ‘I want to do that!’” she said.

Martinez first rang the bells in the Administration Building’s northeast tower on after a Tech soccer win.

“I nearly started crying because there’s something powerful about ringing those bells.”

“I nearly started crying because there’s something powerful about ringing those bells,” said Martinez, president of High Riders for the 2022-23 school year.

Saddle Tramps are Born

In the mid-1930s, Tech students had spirit – but not channeled in the right direction.

The student body was overly exuberant, unorganized and unruly. Private property was destroyed during bonfires and parade-like snake dances.

Arch Lamb, Tech’s head cheerleader, came up with an idea for an organization to guide that enthusiasm in less destructive ways.

The Saddle Tramps were born in 1936.

Early Texas ranchers hired a “saddle tramp” to help, who’d move on after the work was done.

Saddle Tramps would be hard workers when in school at Tech, moving on after their college years were done, Lamb thought.

Lamb has been out of school four years before entering Tech in 1934. He lived in West Hall, where he operated a shoeshine stand and worked in the Tech Creamery. He went on to become a Lubbock County Commissioner.

The group had ten members, up to 50 by the spring of 1937, with a goal of serving in any way to elevate the college in the public’s eyes. The first Tramps wore dark slacks and red shirts dyed in the Textile Engineering Building.

High Riders are Born

Nancy Neill, High Riders’ first president, attended some Saddle Tramp smokers as a hostess fall of 1975 and questioned why there was no women’s organization to support Texas Tech women’s athletics.

She found out there had been unsuccessful attempts.

With friend Lyn Morris they came up with the name and a constitution submitted to the Dean of Students’ Office, making it clear they would count on the help and guidance of God.

On Feb. 2, 1976, the High Riders became an official campus organization.

Sponsors were Joyce Arterburn of the physical education department and B.J. Marshall of the Physics Department.

The by-laws, pledge program, and pledge manual were prepared. The High Rider symbol was designed. T-shirts, bumper stickers, jackets and uniforms were prepared for the first pledge class.

Neill, Morris and now joined by Kathy Pate contacted the Women’s Athletic Council to present the organization to their service. The council immediately put the “founders” to work.

They learned what’s involved in supporting women’s athletics by attending home games, traveling to road games with teams and encouraging the athletes with signs, special treats and send-offs.

During fall rush, approximately 75 undergraduate women attended rush parties and 25 were chosen to be the charter pledge class.

Saddle Tramps Traditions

Midnight Raiders: Every Thursday night before a home football game, the Saddle Tramps wrap the Will Rogers statue at Memorial Circle with crepe paper. Streamers are also hung from the coaches’ bridge, the Frazier Alumni Pavilion and light poles all over campus. At midnight, after Will is wrapped, the Saddle Tramps circle Soapsuds to sing the “Fight Song,” “Matador Song,” Saddle Tramps song and pledge class songs. Some High Riders like to help with this Saddle Tramp tradition, said Martinez.

Bell Circle: The Saddle Tramps open every home football game with a bell circle, welcoming the team on and off the field and start the Go, Fight, Win chant. They also do a version for basketball and baseball. The handbells are unique to every Saddle Tramp, said Bell. “You get to wrap the handle however you’d like because you’ll get blisters if you don’t. They also have a plaque on each one with your big brother and little brother and the year you pledged. When you leave, you get a holder so you can mount it on the wall and have a keepsake,” he added.

They participate in the homecoming parade, during which members run behind , and perform bell circles at every intersection. “We build the bonfire, which is our big thing. We get up at 5 a.m. and start stacking pallets. It’s a whole two days of work,” said Bell, adding Saddle Tramp alumni donate the pallets.

The Saddle Tramps ring the victory bells for 30 minutes after every football, basketball, and baseball win. “A lot of people don’t realize there are people up there physically ringing the bells and they are not motorized or on some sort of timer,” said Bell.

The Statues: Whenever a big rival comes for a home football game, the Saddle Tramps guard the statues on campus.

Saddle Tramp Jim Gaspard created mascot Raider Red in 1971 and only Saddle Tramps or High Riders can be the mascot. Raider Red attends men’s and women’s athletic events, pep rallies, and visits elementary and high schools.

The Saddle Tramps start this ceremony with a torch-lighted parade, which precedes seasonal music and the lighting of campus on the first Friday of December. Longtime Saddle Tramps sponsor Bill Dean turned on the lights at the first Carol of Lights when he was a student in 1959.

The group also:

- Helped plant thousands of trees at Tech’s first Arbor Day in 1938.

- Raised money to buy 40 band uniforms by selling tickets to a band concert.

- In 1978, along with other student groups, broke the world record at the time for an outdoor balloon release letting 151,000 balloons fly at the Tech-SMU football game at Jones Stadium.

- Played a role in obtaining the seal at the Broadway entrance to campus.

- Helped the dream of a student recreation center become reality.

- Set up the Saddle Tramp Student Endowment Scholarship Fund.

- Donated to the Dairy Barn renovation.

“We’re a spirit organization, but we’re also a service organization.”

“We’re a spirit organization, but we’re also a service organization,” said Bell.

Bell is a computer science major from Midland, who came to football games before college.

“It just seemed like this was where I was going to go. All my friends wanted to go. I really enjoyed the culture of Tech,” he said.

Bell didn’t know much about the Saddle Tramps, but one of his friends was going to a rush event and he went along.

“I ended up having a real good time, decided I wanted to join and fell in love with it,” he said.

Saddle Tramp pledges must learn about Tech’s history and traditions and are tested on it.

Pledges go through a process ending with the entire group deciding if a pledge will wear the red workshirt and get their bell.

“We have to make sure we only have people in the organization who are going to try their hardest to keep our traditions going,” he said.

High Riders Traditions

Banquet: A High Rider banquet is held every five years to celebrate the founding of High Riders. Alumni and founders come to a formal dinner.

Spirit Tunnels: High Riders form a spirit tunnel when Tech teams come on the field or court and ring their High Rider Bell.

High Rider Bell: The newest tradition is the handbell. The bells are brought to all games to be used during appropriate times.

High Riders ring the Victory Bells after every home win by womens’ teams. “But when Raider Red won the national championship, Saddle Tramps and High Riders went up there to ring Victory Bells together,” said Martinez.

Big/Lil: A night where pledges find out who their Big Sisters are.

High Riders light the path for the Saddle Tramps.

Homecoming: High Riders participate in the homecoming parade, so-sing, spirit board, spirit banner and are in charge of the pep rally.

High Rider Katie Lynn was the first female Raider Red in 2005.

Locker Decorations: High Riders decorate locker rooms of women’s athletic teams before some games.

Martinez grew up in Lubbock and graduated from Lubbock High School’s demanding International Baccalaureate program.

She attended various Tech sporting events and participated in some Tech soccer camps.

Martinez had heard of the Saddle Tramps.

After she came to Tech’s Honors College, a friend told her about High Riders.

The group is passionate about supporting women student athletes because they don’t get the same attention as men’s teams – now and historically.

“Why didn’t I hear about this opportunity growing up? There’s a group for women’s athletics too?” she said, adding the group is passionate about supporting women student athletes because they don’t get the same attention as men’s teams – now and historically.

“Where the Talkington dorm is now there used to be a gym and that’s where women’s basketball played. They weren’t allowed to use the Coliseum,” she said of the dark ages of women’s college sports.

High Riders have about 40 members and Martinez wants to grow that to 50 or more this coming school year.

Much like their male counterparts, the High Riders learn about Tech’s history and traditions.

She also wants to get the word out about the High Riders so more people aren’t surprised like she was.

Mission Hasn't Changed

The original mission to show sportsmanship and class is still important to both groups.

From the Saddle Tramps list of do’s:

- Start a chant or yell when boos come from the student section.

- Face the flag with right hand on heart and left hand with “Guns Up” through back belt loop during the “National Anthem.”

- Be polite to our opponents, including cheerleaders, fans and players.

- Put Guns Up when an injured player is on the playing surface.

From the Saddle Tramps list of don’ts:

- Downgrade the teams, players or coaches.

- Harass the officials.

- Drink alcohol while wearing official Saddle Tramp dress.

- Ring bells during a band song, announcements, awards, while on the field during play or when any players are injured.

The group didn’t have to get the crowd excited last Feb. 1, when the Texas basketball team came to Lubbock with former Tech head coach Chris Beard leading the Longhorns.

“There were extensive meetings before, talking about how we needed to behave. We needed to be the example during the game, try to keep things under control and make sure everybody stays safe,” said Bell.

Sources:

- Saddle Tramp Manual

- High Riders Manual

1936: Victory Bells Donated, Start Ringing

Arch Lamb – “father” of the Saddle Tramps – promised to ring the Victory Bells all night on Sept. 26, 1936. The Red Raiders hosted the defending national champion TCU Horned Frogs before a crowd of 12,000 in Lubbock.

Tech won 7-0, shutting out TCU’s legendary quarterback Sammy Baugh, who months later was the 7th overall pick in the 1937 NFL Draft.

It was one of Tech’s earliest “signature” wins.

Lamb climbed to the Administration Building’s east tower and started ringing the bells…and ringing…and ringing.

Residents got annoyed, because they couldn’t sleep, Ben Montecillo, a Saddle Tramp alum, told the Daily Toreador student newspaper in 2021.

“They were trying to get him out of the bell tower, but he had barricaded himself and some of his other Saddle Tramps at the time in the bell tower,” Montecillo said. “They said they wouldn’t stop and were threatened with expulsion and they still refused. They said, ‘A promise is a promise and that’s what we’re going to do.’”

They rang until 6 a.m. the next day.

Within a day or two, it was decided the bells could ring for no more than 30 minutes.

The class of 1936 gave the Victory Bells as their gift to Tech. They rang for the first time at the group’s graduation and were silent until a few months later when Lamb rung up Lubbock.

The bells – one large and one small with a combined weight of 1,200 pounds – ring after:

- Tech football, basketball or baseball wins.

- Tech teams win a Big 12 Conference title.

- A Red Raider is selected as an All-American.

- A Tech commencement ceremony ends.

- Tech students are recognized during honors ceremonies.

They’ve also rung for special occasions – when Tech joined the Southwest, and a few decades later, the Big 12 conferences.

The bells rang 41 times when President George H.W. Bush – America’s 41st president – died in 2018.

Saddle Tramps and High Riders manually ring the bells, pulling chains.

The Victory Bells were Kent Hance’s favorite tradition as a student.

Now he’s Tech’s chancellor emeritus.

But in 1962 he was a Saddle Tramp pledge charged with ringing the bells with fellow pledge Tom Craddick.

Craddick became speaker of the Texas House of Representatives.

But decades back, they were pledges following orders.

Tech’s ’62 football team ended up with a 1-9 record in coach J.T. King’s second year. The Red Raiders were hosting Texas and well behind at halftime in a game they ended up losing 34-0.

“And that’s back when nobody scored that much,” said Hance.

“But the president of the Tramps was the most optimistic guy in the world and at halftime he sent us over to (the Victory Bells) to get warmed up,” said Hance, who didn’t get to ring the bells that day.

Sean Cunniff rang the bells in 2007 when Texas Tech knocked off No. 3-Oklahoma at Jones AT&T Stadium.

“When they ring, I am proud to be a Red Raider. It means Texas Tech took care of business.”

“They told me I had to learn how to ring the bells that day. At first I was upset because I would have to miss the end of the game, but we got up in the bell tower and turned on the radio. We listened while Texas Tech beat Oklahoma and then we started ringing the bells,” he said. “When they ring, I am proud to be a Red Raider. It means Texas Tech took care of business.”

Sources:

1938: Arbor Day Tradition Planted on Campus

Texas Tech wasn’t carved out of deeply forested land.

And in the school’s first years of life, the focus was on getting academic programs started and constructing buildings where those programs would be implemented. There wasn’t a lot of time or money to think about sprucing the campus up a bit on the flat, almost treeless South Plains.

In 1938, Bradford Knapp, Tech’s second president, proclaimed one day each spring should be dedicated to changing that.

On March 2, 1938 – Tech’s first Arbor Day – classes were dismissed at noon and 20,000 trees and shrubs were planted by faculty, staff and more than 1,000 members of student organizations.

Shrubs, hedges and more than 50 varieties of trees from the Tech nursery were planted according to blue-printed plans.

O.B. Howell, professor of horticulture, had advanced horticulture students as foremen in charge of moving trees, water hoses, stakes and tools. Some faculty and staff were “straw bosses” to direct the planting around buildings. Five mounted supervisors kept an eye on the work.

A chuck wagon served coffee and doughnuts.

“In not more than or four years the campus will be practically transformed,” said Howell, pledging to make the effort an annual event.

The good news? Tech improved the campus in one day.

The bad news? There were no resources to care for the plants the other 364 days of the year and many died from neglect.

Arbor Day continued for another ten years.

There are photos of President Clifford B. Jones watering a shrub and supervising tree planting while on a horse.

Tech eventually was able to expand its maintenance program and hire Elo Urbanovsky, a landscape architect. Under Urbanovsky’s leadership, the campus was transformed.

Arbor Day started in America decades before Knapp brought the idea to Lubbock – in 1872 in then-barren Nebraska.

Arbor Day returned to Tech as an annual activity when Debbie Montford, wife of Tech’s first chancellor John Montford, focused on campus beautification. It continues, held the last Friday in April.

It didn’t take place in 2020 because of the COVID pandemic, but in 2021, Tech was planting again, with a scaled-down effort because of the pandemic.

About 500 people helped plant about 26,000 growing things.

“Usually when people think of Arbor Day they think of planting trees,” Troy Pike, activities coordinator for Student Union and Activities, told the Daily Toreador, Tech’s student newspaper in 2021. “We are not going to plant trees; we will be planting flower beds instead. We will be planting at the Broadway entrance, Memorial Circle, the Engineering Key and the Tech Administration Building. We have been doing this now for the past 22 years.”

“We know this campus is absolutely beautiful and the grounds maintenance does a ton of work all year long to make it look great.”

“I think Arbor Day is a great way to give back,” Pike told the DT. “We know this campus is absolutely beautiful and the grounds maintenance does a ton of work all year long to make it look great. This is a good way to realize the semester is coming to an end, so everyone should do what they can to make campus look great for graduation and for the last couple weeks.”

Arbor Day is not only a celebration of campus, but a way for students, faculty and staff to come together and strengthen the sense of community, Bethany DeLuna, a senior history major from Wichita Falls, told the Toreador.

“The campus belongs to all of us, so I think it’s nice to have a hands-on experience in making campus beautiful as well as forming that community bond with everyone working together,” DeLuna said.

More than 100 student groups get involved with Arbor Day.

“We participate in Arbor Day every year either individually or as a whole organization,” Stacy Stockard Caliva, the Tech High Riders advisor, told the Toreador. “One of our main values is serving the Tech and Lubbock community, so we’re always looking for ways to contribute.”

Grace Howard, a junior natural resources management major from Tyler, told the Toreador Arbor Day is a good way to make friends.

“It’s an amazing thing to continue to make our campus beautiful…it feels like everyone is coming together, regardless of being in different majors or organizations. I’ve actually met several of my friends through Arbor Days in the past.”

In 2022, there were almost three-dozen spots on campus where Tech continued this long tradition of planting beauty.

Sources:

- The Southwest Collection’s Texas Tech in Retrospect…Arbor Day: An early Tech tradition

Daily Toreador:

1950: Will Rogers & Soapsuds Statue Dedicated with Its Rear End Aimed at Texas A&M

A man only learns in two ways, one by reading, and the other by association with smarter people. – Will Rogers

Humorist-philosopher Will Rogers was speaking to a Lubbock crowd on Oct. 29, 1926.

Rogers knew all about Texas Technological College, its football team and coach, he said. Rogers added he assumed the college had a president, but he’d never heard of him.

That night, Rogers was getting on a train for Fort Worth. So was Tech President Paul Whitfield Horn. Some Lubbock folks made sure they met.

“Mr. Horn, please excuse that bum joke of mine. Of course, I’ve heard lots about you,” it was reported Rogers said.

The comment did more to credit Rogers’ courtesy than veracity, Horn said.

Tech was scheduled to play Texas Christian the next Saturday.

According to the Fort Worth Star-Telegram:

“Will Rogers wants Fort Worth to see a ‘real West Texas band’ and hear some real West Texas music. That’s the reason he gave $200 to help bring the 80-piece band of Texas Technological College to Fort Worth for the game with TCU Saturday.”

Minutes of the Oct. 30, 1926, Tech Board of Directors include the item:

“Chairman (Amon) Carter presented a check signed by Will Rogers for $200 and one by himself for $100 as contributions toward the expenses of bringing the College band to Fort Worth…for the TCU football game.”

The Goin’ Band was launched. Unfortunately, Tech lost its first showdown with a future Southwest Conference opponent, 28-16.

Carter was a newspaper publisher, oil man and first chairman of Tech’s Board of Directors – and a good friend of the popular Rogers.

Nine years later, Rogers died in an Alaskan plane crash with another friend, famed pilot Wiley Post.

On Feb. 16, 1950, 15 years after Rogers died, a bronze statue of him riding his horse Soapsuds was dedicated on the Tech campus. It was a gift from Carter, who passed away five years later.

The statue’s details:

- 9-feet, 11-inches tall

- 3,200 pounds

- $25,000 estimated cost

- On the base of the statue, the inscription reads, “Lovable Old Will Rogers on his favorite horse, ‘Soapsuds,’ riding into the Western sunset.”

It’s one of three cast at Carter’s request: One at the Will Rogers complex in Fort Worth and one at the Will Rogers memorial in Claremore, Oklahoma, close to his hometown of Oologah.

“This statue will fit into the traditions and scenery of our great western country. Will Rogers felt at home in the Lubbock section. He punched cattle not far from this site. His statue is a befitting monument to your students and faculty,” said Carter.

One of Rogers’ favorite ranches was the Mashed O spread owned by Ewing Halsell, west of Lubbock. His last visit to the Mashed O was in 1935, shortly before he died.

Even though Rogers’ connection to Tech is minimal, the statue has become one of Tech’s beloved landmarks.

Even though Rogers’ connection to Tech is minimal, the statue has become one of Tech’s beloved landmarks.

There’s great folklore of why the horse’s rear end is pointed in a certain direction and the Saddle Tramp practice of wrapping the statue in red crepe paper for home football games has become one of Tech’s great traditions.

The statue has also been wrapped in black crepe paper to mourn national tragedies.

Ruth Horn Andrews, in her book, “The First Thirty Years” wrote:

“The statue, called “Riding into the Sunset,” was done by Electra Waggoner Biggs of Texas and New York. The humorist-philosopher and Soapsuds, his mount, look as much at home on the esplanade leading up to Memorial Circle on the campus as young cowpoke Rogers undoubtedly felt when, about the turn of the century, he rode the range of the Halsell Ranch, not a great distance from where his effigy now stands. So much a part of the Tech scene has Will Rogers and Soapsuds become that the cover of the 1955 volume of La Ventana bears a representation of the statue.”

In November of 1951, the Texas Tech Museum and the Lubbock County Sheriff’s Posse celebrated Rogers’ birthday. A parade started at the fairgrounds and ended at the statue where a wreath was place around the neck of Soapsuds. Brownie McNeil, a singer and guitarist from San Antonio, presented a recital of cowboy ballads in the Museum auditorium.

As for Soapsuds’ posterior:

According to one legend, the plan to face Will Rogers so he’d ride into the sunset didn’t happen because Soapsuds’ rear would be facing downtown. To solve this problem, the statue was turned 23 degrees to the southeast so the horse’s rear end was facing in the direction of College Station, home of rival Texas A&M.

Another legend is if a virgin graduates from Texas Tech, Rogers will dismount. When a visiting alum says, “I see Will is still on his horse,” the implication is supposedly understood.

Sources:

- “The First Thirty Years” by Ruth Horn Andrews

- “The Southwest Collection’s Texas Tech in Retrospect: Will and Soapsuds” by Michael Q. Hooks

1954: Joe Kirk Fulton: First Masked Rider

Before the Masked Rider, Texas Technological College had the Ghost Rider.

In 1936, George Tate wore a mask and scarlet cape on a Palomino named Tony before a football game against TCU and its star quarterback Sammy Baugh.

Tate and Tony didn’t hang around long enough to become a tradition.

In 1953, the Red Raiders were having a great football season, hoping the on-the-field success would boost their resume to get into the Southwest Conference. All SWC teams had a mascot and Tech felt it needed one.

Around that time, Joe Kirk Fulton rode a horse into the Student Union as a prank. It wasn’t funny to the rodeo team that was suspended because it was assumed one of them was guilty.

Football coach DeWitt Weaver knew Fulton’s dad and asked if his son would be interested in creating a mascot.

They met.

“Would you be the first Red Raider?” Fulton, in a 2011 interview, said Weaver asked him.

Yes, he told the coach.

Fulton had chaps made at Wendy Ryan’s in Fort Worth, part of his ensemble. He borrowed a black horse from the Hockley County Sheriff’s Posse.

His debut was at the Gator Bowl on Jan. 1, 1954, in Jacksonville, Florida, when the 10-1 Red Raiders faced Auburn.

Fulton led the team on the field, under a black hat with his red cape flying.

“No team in any bowl game made a more sensational entrance,” wrote Ed Danforth of the Atlanta Journal.

Tech beat Auburn 35-13 to finish the season 11-1 and ranked 12th in the nation.

The name Red Raider became Masker Rider and Fulton served as the mascot the next school year.

During that year, Tech was playing LSU and Fulton collided with an LSU cheerleader. Weaver told his mascot:

“I don’t care how many cheerleaders you run over. Just make sure you get the quarterback first,” Weaver said.

Sixty students and more than a dozen black horses have followed Fulton – who passed away in 2013 – giving Tech a mascot and enduring symbol.

Picking the Masked Rider

Most years, about a dozen upperclassmen apply to be the Masked Rider, said Stephanie Rhode, Tech’s Spirit Program director.

An arduous process begins in January with background checks. Then:

- A written equestrian test. Sam Jackson from Animal Sciences puts it together and Rhode contributes questions about Texas Tech. A score of at least 80 percent is needed to advance.

- Candidates submit references, answer ten questions about their background, put together a portfolio of their experience with horses, public speaking and other needed skills.

- They ride a horse.

- They drive a truck and horse trailer.

After that, about three-to-five students are finalists.

“Then we have them interview with the Masked Rider Advisory Committee, made up of about 25 people. That’s a pretty in-depth interview,” said Rhode. “We gather all the scores and choose a mascot by the end of March.”

Rhode’s amazed how many students want to do it.

“It’s a full-time job,” said Rhode, who feels like she’s the Masked Rider’s on-campus mom during their year.

The Masked Rider used to get a $3,000 stipend, but now gets a full-ride scholarship. The Linda and Terry Fuller Masked Rider Scholarship Endowment was established in 2013 by the Fullers, one of the couple’s many philanthropic gifts to their alma mater.

There’s a transition period of a few weeks before the new Masked Rider is introduced at the Passing of the Reins ceremony.

“You get fitted for your uniform, work with the current rider on the transition,” said Stacy Stockard Caliva, Masked Rider in 2004-05, taking over from Ben Holland.

She went to appearances with Holland to see what happens, help and started riding Midnight Matador.

“That’s the main part, getting to know the horse. Then when we transfer the reins, it’s truly a transfer of the reins,” she said. Caliva got the horse and keys to the truck, trailer and barn.

The next day Caliva was riding in her first appearance, a Lubbock parade.

“You wake up every morning, the first thing you do after you get ready is tend to the horse. You go study and do your assignments. You feed the horse dinner. Sometimes you go check on him later at night,” she said.

The Masked Rider is responsible keeping the horse exercised, groomed and maintaining the truck and trailer.

“When you put on that hat and do the transfer of reins, you are no longer embodying yourself, you’re really taking on a role in the service of Texas Tech.”

“When you put on that hat and do the transfer of reins, you are no longer embodying yourself, you’re really taking on a role in the service of Texas Tech. You get to represent the university as an icon that a lot of people associate with their time at Texas Tech,” she said.

“You’re joining this pretty small group of people who know what that role is really like from the inside. What it’s like to knock out a stall and then have to go to a chemistry lab. Or how hot it gets under that cape during summer rodeos and parades and how that cape makes a wonderful blanket on those cold, November football games,” she said.

Masked Riders also know about connecting with their equine partner.

“They know what it’s like to have this strong bond with a horse. I’m pretty biased but I think they are really some of the coolest horses on the planet,” she said.

Almost 20 years later, she looks back on that time.

“The students who step into that role are outstanding students who are one of the most public faces of the university and take care of our horses so many people hold dear. It’s a testament to the quality of students we have here at Texas Tech,” she said.

Picking the Horse

Sam Jackson was planning on going to Texas A&M when the Masked Rider and Happy VI-II made what turned into a recruiting visit to his family’s spread in Stephenville.

“My father was good friends with the father of Kurt Harris, the Masked Rider,” said Jackson.

They were looking for a place to spend the night where they could keep the horse on the way to the Baylor game. This was when the horse went to most Southwest Conference games. Harris was traveling with his assistant Perry Church, who would take the reins the next school year.

Jackson went with them to the Baylor game and helped.

“That experience was one of the things that convinced me to attend Texas Tech instead of Texas A&M,” he said. “I was able to visit with those two. They were Animal Science majors, I was going to be an Animal Science major and they were outstanding people. They told me about the department, that led me to come up here, visit with faculty and cement the deal.”

While at Tech, Jackson was on national championship Livestock Judging and Wool Judging teams. He did go to A&M for a master’s degree before returning to Lubbock for his Ph.D. He’s associate chair and associate professor in the department of Meat Science & Muscle Biology and coordinates the Wool Judging Team.

Jackson took over the horse side of the Masked Rider program in 1995.

Rhode oversees the rider, schedules hundreds of appearances.

Jackson makes sure the horse is doing well.

He’s also in charge of picking the horse. If Masked Rider candidates think the process Tech puts them through is hard, the horse would disagree.

Less than 1 percent of horses have a shot at becoming the Masked Rider’s mount.

Less than 1 percent of horses have a shot at becoming the Masked Rider’s mount.

Jackson finds horses through a network of alumni, friends, people who knows what qualities the horse must have.

“Somebody will say ‘I just ran across a good, black horse. You want to look at it?’ I’ll say, yeah, give me his contact info. That’s how we found Fearless Champion,” said Jackson, about the horse that just retired after serving nine years.

Jackson got the tip from an old friend and former Masked Rider – Perry Church – who visited Jackson’s Stephenville home with Kurt Harris back when Jackson thought he’d be an Aggie.

“He called and said, ‘we branded up around Pampa and this guy’s got a pretty nice black horse I think could work as the Masked Rider horse.’ He gave me the guy’s number. I went up, started evaluating the horse and he ended up being Fearless Champion,” said Jackson.

That’s just the start of Jackson’s process:

- The horse must be black.

- Breed is important. “A lot of people have this perception we just need a beautiful black stallion. That’s the furthest thing from the truth. I get calls about Andalusians and Arabians – breeds that usually don’t have the mentality to be able to handle the stress,” said Jackson. Tech needs a horse that can stay calm in front of 60,000 screaming football fans. Quarter horses are typically quieter and calmer.

- Quarter horses are also durable, another thing Jackson looks for – checking a horse’s feet and legs. “This horse makes a lot of appearances. Gets in and out of the trailer a lot and goes to a lot of places. You’ve got to have a horse able to handle that much use,” he said.

- Size. “I don’t need a little bitty one – I don’t need a great big one,” he said.

- Experience. “What’s he done, who’s ridden him, what have they done with him,” Jackson added.

- Age – which is explained in a bit.

After getting that information, Jackson decides if the horse is worth seeing. If yes, he takes the horse for a ride.

“Usually after that first ride, I have a pretty good idea,” he said, adding he can very quickly tell if the answer is no.

“A lot of people have this perception their horse is really broke, quiet and talented. When I get on him and ride him it’s very obvious to me as somebody who’s ridden a jillion horses that he’s not broke, he’s not quiet. When I ask him to do certain things and he responds in a certain way I know he’s problematic.,” said Jackson.

It might be the horse is just young and inexperienced.

“But it also may be that he’s just not a horse that’s been trained and prepared properly, that I would feel comfortable with. I know the skill set that horse needs and what they need to be able to do,” he said.

If a horse passes all that scrutiny, Jackson brings them to campus for two reasons.

“One, get them away from their owner. You never know what the owner has done ahead of time to prepare a horse for purchase. I’m not saying most people are unethical, but some people drug them. They’ll give the horse a tranquilizer before you get there,” he said.

The horse seems calm during the ride. Then the drug wears off eight hours later and he’s totally different, said Jackson.

“So we get him to campus and under our control so we can see what he is naturally. They may have ridden him before we came three straight days for five hours every day. The horse is tired, wore out and it makes him quiet,” said Jackson.

Then, two, the horse meets the stimuli it could encounter at a football game.

“That starts with the band. We go to band practice and that’s very telling. Most of them do not pass band practice. I don’t know if it’s the drums, but a lot of horses are very intolerant of that experience,” he said.

If the horse hits all the right notes at band practice, the next step is a football game.

In 2012, Tech had already finished its regular season when they were taking Fearless Champion through the process. They took him to Tech’s bowl game against Minnesota in Houston’s indoor Reliant Stadium.

“This horse had never been to a football game. But he had done so well I felt it didn’t matter if I was going to test him in that environment or in Jones Stadium,” said Jackson.

Tech was leasing the horse while deciding if he’d be a long-term horse.

Some fireworks and a cannon went off.

“The horse was quiet and solid as when we walked him out of the trailer. We bought the horse,” he said.

Tech pays somewhere between $5-10,000 for a horse, said Jackson. Sometimes an alum will sell a little lower.

Jackson had a horse from New Mexico that got all the way to the football game.

“We had a horse we were ready to retire,” said Jackson. They brought in the new horse at halftime at a packed Jones AT&T Stadium against Texas.

“The stadium had that big-game buzz,” said Jackson.

The horse got a few feet onto the field, started jumping, kicking and running backwards.

“Just a total abandonment of behavior. We got him out of there and this horse is sweating. There was no indication the horse would respond like that. He just couldn’t tolerate it. He didn’t pass the last test,” said Jackson.

Midnight Matador and Fearless Champion served the last 20 years, but Jackson said most horses don’t last that long.

“Usually when a horse reaches a point in his life where he’s broken and calm enough he’s got some age on him,” said Jackson, saying the horse could be 10-15 years old by then. Midnight Matador went a record 11 years, but started when he was three, which is unusual. When Midnight Matador retired, Caliva kept him until he died in 2015.

“It doesn’t matter what you’re doing with them, roping cattle, barrel racing – they don’t last forever,” said Jackson, saying the average time a horse can serve in the program is five years. “I don’t think we’ll ever have another horse go 11 years.”

Their feet get sore, their muscles get sore.

“They’re no different than an aging person,” he said.

Fearless Champion had to sit out a game due to an injury a few years ago and he didn’t recover as quickly as he would have a few years earlier. There is no back-up horse.

“If you’re a barrel racer and your horse gets sore, you don’t barrel race. But if this horse is sore and he doesn’t make an appearance, it’s a big deal,” he said.

Incidents Happen

The Masked Rider’s history has not been without incidents:

- 1963: Tech Beauty was kidnapped and spray-painted with the letters “AMC” prior to Tech’s football game against rival Texas A&M.

- 1975: Happy Five was kidnapped and received chemical burns after being painted with orange paint before Tech’s football game against Texas.

- 1982: The Masked Rider was involved in injuring an opposing school’s cheerleader. Ten years later, the Masked Rider was involved in injuring a referee.

- Tragedy struck in 1994: Masked Rider Amy Smart’s saddle broke during a post-score gallop. Double T got scared, ran into the tunnel, hit the wall and died instantly. Smart broke her arm when she was thrown off.

Then-Tech President Bob Lawless banned future running of the mascot and a committee was created.

A new horse and rider were ready the following year, but the mascot was still not allowed to run because of the committee’s moratorium.

After John Montford became chancellor in 1996, he knew people wanted the horse to run again.

“I attended a meeting of the solemn Committee for the Masked Rider and pleaded my case, requesting that the horse be allowed to run at the opening of the game when the teams took to the field but not necessarily after each Tech touchdown, which I felt was a reasonable compromise,” Montford wrote in his book, “Board Games: Straight Talk for New Directors and Good Governance.”

The committee went into executive session and after a long deliberation, the committee chair came into the hall and told Montford the group had voted and the horse was not going to be allowed to run.

“This committee is dissolved,” Montford replied.

The horse ran in the next game when Texas Tech beat Baylor 45-24 in front of a crowd of 50,000 and “erupted with applause when the horse and its Masked Rider took the field.”

One other horse in the program had to be euthanized when the Masked Rider was driving and hauling the trailer. Another vehicle came into the lane. The Masked Rider tried to avoid an accident but couldn’t.

Over the years, Masked Riders rode with a certain panache.

Before the low wall was built around Jones Stadium, Masked Riders would ride up the grass area above the north end zone, picking up speed as they galloped back down.

Some Masked Riders put the reins in their mouth and flashed a Guns Up sign with both hands.

That’s not allowed anymore.

“That’s probably one of the things I say within the first five minutes when I meet these students. We don’t do that anymore – we want to maintain our insurance,” said Rhode.

Now Masked Riders have one hand on the reins and one hand doing Guns Up.

Every August there’s a safety meeting to go over what happens if there was another incident like in 1994. A veterinarian is at games with drugs to euthanize the horse if needed and equipment is in place to remove the horse quickly.

Jackson – who joined the program the year after the horse died – points out over the almost 70 years of the program, incidents have been remarkably low.

“…We really have not had that many negative events. I think that’s because of good riders and good horses.”

“When you look at a tradition that is this old and has many opportunities for problems when you think about how many appearances the Masked Rider makes – we really have not had that many negative events. I think that’s because of good riders and good horses,” he said.

‘It Never Gets Old’

The Associated Press ranked the Masked Rider the ninth-best mascot in college football in 2010 and Tech’s pre-game entrance is consistently ranked among the ten best in the country.

“It never gets old to me,” said Rhode. “I will talk to men who remember it back in the ’60s and they’ll tear up about about it, what it means to them, how symbolic it is of this university we all love. That really gets to you.”

Jackson wonders how many others, like him, came to Tech after seeing the Masked Rider.

“How many thousands of students were impacted by the Masked Rider in their town at a rodeo, parade or at a football game?” he said.

‘Dad was so Honored’

Joe Kirk Fulton took over his family’s oil, banking and ranching business but was always proud of kicking off the Masked Rider.

“Dad was so honored they chose him to be the first Masked Rider,” said his son Tim, who now oversees the family businesses out of a Lubbock office.

“He was larger than life. He was my hero,” said Tim.

Sometimes his dad’s history comes up during a conversation. “Everybody’s in such disbelief. They’ll say, ‘that is so neat.”

Every Masked Rider loved horses, but Fulton was on another level.

Every Masked Rider loved horses, but Fulton was on another level, said his son. Fulton was involved with cutting horses, quarter horses and passionate about breeding.

“Dad loved to go fast,” said Tim. His dad was inducted into the American Quarter Horse Hall of Fame in 2011.

They raced horses and still do – with trophies spread around Tim’s office.

His dad and mom, Merle, were friends with another former Masked Rider – Kurt Harris – the same Masked Rider who visited Jackson’s home years ago and became an equine veterinarian.

A few years after Fulton passed away, Merle married Harris.

Tim and his mother share Joe Kirk’s passion for genetics.

They even tried to breed a horse for the Masked Rider program.

“Getting an all-black horse is hard. We studied all these stallions, looking for a specific gene that could produce an all-black horse. We found a horse and bred it to a foundation mare my mother had. But he ended up with four white feet and a star on his blaze,” he said.

When Joe Kirk died, Masked Rider Corey Waggoner brought Fearless Champion to the funeral. Boots were sideways and backwards in the stirrups to honor the first Masked Rider.

On the 60th anniversary of Joe Kirk’s first ride, shortly after his death, Merle said:

“It’s very emotional for me. I feel very honored. He always said he never dreamed him riding the horse was going to be a legacy for Tech, and it is. It’s very emotional for me every time I see that horse.”

Masked Riders and their Horses

- 1953-54: Joe Kirk Fulton/Lubbock, Texas

- 1954-55: Joe Kirk Fulton/Lubbock, Texas

- 1955-56: Jim Cloyd/Stratford, Texas/Blackie

- 1956-57: Jim Cloyd/Stratford, Texas/Tech Beauty

- 1957-58: Donald “Polly” Hollar/Benham, Texas/Tech Beauty

- 1958-59: Donald “Polly” Hollar/Benham, Texas/Tech Beauty

- 1959-60: J.H. “Hud” Rhea/Roswell, N.M./Beau Black

- 1960-61: J.H. “Hud” Rhea/Roswell, N.M./Beau Black

- 1961-62: Kelley Waggoner/Hillsboro, N.M./Tech Beauty

- 1962-63: Bill Durfey/The Woodlands, Texas/Tech Beauty

- 1963-64: Douglas “Nubbin” Hollar/Brenham, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1964-65: Douglas “Dink” Wilson/Quanah, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1965-66: Douglas “Dink” Wilson/Quanah, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1966-67: Douglas “Nubbin” Hollar/Brenham, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1967-68: Douglas “Nubbin” Hollar/Brenham, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1968-69: Johnny Bob Carruth/Lubbock, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1969-70: Johnny Bob Carruth/Lubbock, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1970-71: Tommy Martin/Graham, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1971-72: Randy Jeffers/Amarillo, Texas/Charcoal Cody

- 1972-73: Randy Jeffers/Amarillo, Texas/Showboy Huffman

- 1973-74: Gerald Nobles/Midland, Texas/Happy Five

- 1974-75: Anne Lynch/Dell City, Texas/Happy Five

- 1975-76: Joe Kim King/Brady, Texas/Happy Five

- 1976-77: Jess Wall/Perryton, Texas/Happy Five

- 1977-78: Larry Cade/Copperas Cove, Texas/Happy Five

- 1978-79: Lee Puckitt/San Angelo, Texas/Happy VI

- 1979-80: Coke Topping/Memphis, Texas/Happy VI

- 1980-81: Kathleen Campbell/El Paso, Texas/Happy VI-II

- 1981-82: Kurt Harris/Collinsville, Texas/Happy VI-II

- 1982-83: Perry Church, Canyon, Texas/Happy VI-II

- 1983-84: Jennifer Aufill, Buffalo Gap, Texas/Happy VI-II

- 1984-85: Zurick Labrier/Guymon, Oklahoma/Happy VI-II

- 1985-86: Jerrell Key, Lubbock, Texas/Happy VI-II

- 1986-87: Daniel Jenkins, Turkey, Texas/Happy VI-II

- 1987-88: Kim Saunders/Colfax, Louisiana/Midnight Raider

- 1988-89: Lea Whitehead/Midland, Texas/Midnight Raider

- 1989-90: Tonya Tinnin/Bryson, Texas/Midnight Raider

- 1990-91: Blaine Lemons/Colorado City, Texas/Midnight Raider

- 1991-92: RaLynn Key/Crosbyton, Texas/Midnight Raider

- 1992-93: Jason Spence/Seminole, Texas/Midnight Raider

- 1993-94: Lisa Gilbreath/Lewisville, Texas/Double T

- 1994-95: Amy Smart/Midland, Texas/Double T

- 1995-96: JoLynn Self/Lubbock, Texas/High Red

- 1996-97: Martha Reed/San Angelo, Texas/High Red

- 1997-98: Becky McDougal/Lubbock, Texas/High Red

- 1998-99: Michael “Dusty” Abney/Lubbock, Texas/Black Phantom Raider

- 1999-2000: Travis Thorne/New Deal, Texas/Black Phantom Raider

- 2000-01: Lesley Gilbreath/Flower Mound, Texas/Black Phantom Raider

- 2001-02: Katie Carruth/Lubbock, Texas/Black Phantom Raider

- 2002-03: Jessica Melvin/Pierre, South Dakota/Midnight Matador

- 2003-04: Ben Holland/Texline, Texas/Midnight Matador

- 2004-05: Stacy Stockard/Stanger, Texas/Midnight Matador

- 2005-06: Justin Burgin/Scurry, Texas/Midnight Matador

- 2006-07: Amy Bell/Kermit, Texas/Midnight Matador

- 2007-08: Kevin Burns/Clovis, N.M./Midnight Matador

- 2008-09: Ashley Hartzog/Farwell, Texas/Midnight Matador

- 2009-10: Brianne Hight/Clovis, N.M./Midnight Matador

- 2010-11: Christi Chadwell/Garland, Texas/Midnight Matador

- 2011-12: Bradley Skinner/Arvada, Colorado/Midnight Matador

- 2012-13: Ashley Wenzel/Friendswood, Texas/Midnight Matador

- 2013-14: Corey Waggoner/Lubbock, Texas/Fearless Champion

- 2014-15: Mackenzie White/Marble Falls, Texas/Fearless Champion

- 2015-16: Rachel McLelland/Tijeras, N.M./Fearless Champion

- 2016-17: Charlie Snider/Corinth, Texas/Fearless Champion

- 2017-18: Laurie Tolboom/ Dublin, Texas/Fearless Champion

- 2018-19: Lyndi Starr/Mount Vernon, Texas/Fearless Champion

- 2019-20: Emily Brodbeck/Lubbock, Texas/Fearless Champion

- 2020-21: Cameron Hekkert/Highlands Ranch, Colorado/Fearless Champion

- 2021-22: Ashley Adams/Lubbock, Texas/Fearless Champion

- Current: Caroline Hobbs/Dallas, Texas/Centennial Champion

1960: Locomotive Bell Becomes Bangin' Bertha

For more than 60 years, the bell has been ringing – thanks to Saddle Tramp Joe Winegar and the Santa Fe Railroad.

The railroad donated a bell designed by Winegar in 1959 and Bangin’ Bertha became a loud Texas Tech tradition.

Saddle Tramps carry Bangin’ Bertha on a trailer to home football and baseball games, plus homecoming events.

The original bell was used into the mid-2010s when it was cracked beyond repair and replaced.

The original bell was used into the mid-2010s when it was cracked beyond repair and replaced.

The Saddle Tramps ring Bangin’ Bertha behind the south end zone at football games at Jones AT&T Stadium.

When Zach Thomas beat Texas A&M with a late pick six to win the 1995 game in Lubbock, he ran into the end zone, out the back line, turned right and was mobbed by his teammates right next to Bertha.

The bell’s traveled to away games, like bowl games.

At football games, it’s rung:

- Repeatedly as the teams run onto the field.

- Repeatedly after each Red Raider score.

- For third – and fourth-down – plays when Tech is on defense. But Saddle Tramps are taught to stop once the opposing team’s center touches the ball.

- It’s also rung by a special guest each game.

For baseball, it’s rung:

- Once for each Red Raider as they exit the dugout at the start of the game.

- Once when a run’s scored.

- At the end of the inning.

- It’s also rung repeatedly for a Tech home run until the runner crosses home plate.

For both football and baseball, it’s rung in sync with the Saddle Tramp bell circle.

Students who ring the bell wear earplugs to protect their hearing.

1961: First Carol of Lights Starts Beloved Tradition

Bill Dean pushed a button to illuminate the 60th Carol of Lights in 2018 – just as he did 60 years earlier as Student Body President.

Back then it wasn’t a button, but a different contraption to turn on about 5,000 lights on a few buildings in front of a few hundred people.

When Dean pushed that button in 2018, he powered 25,000 lights on 18 buildings in front of a much larger crowd that some years grows past 20,000.

The Carol of Lights has become one of Texas Tech’s most beloved traditions, kicking off the holiday season in early December.

The lighted Masked Rider, Saddle Tramps Torch Light Processional and High Riders follow luminaria around Memorial Circle to the Science Quad where the annual program follows – the highlight coming when the lights are turned on.

And Dean – longtime professor, Saddle Tramp sponsor and former head of the Texas Tech Alumni Association – has been to every one rain or shine except when he was in military service in the early 1960s.

“Dr. Gene Hemmle, who was chair of the Music Department, gathered some students in the Quad. They had hot chocolate and sang Christmas carols,” said Dean of the event’s beginning.

In 1959, Harold Hinn, a member of the Board of Regents, came up with the idea to string lights on a few buildings on the Quad and paid for them.

Dean was asked to turn on the lights.

“I thought ‘this is cool,’” Dean remembered thinking.

“It wasn’t much compared to what we have today,” he said, adding he had no idea then what the “Carol” would become.

“It’s a wonderful way to kick off the season. And I think, my God, this thing – when I think back – it’s grown each year and it’s pretty significant. Students seem to love it – and they bring their dogs,” said Dean.

Dean was asked what the audience reaction was when he was introduced in 2018 and people heard about his history with the event.

“Well, the Saddle Tramps all clapped,” he said in his laid-back way.

Growing Up in Lubbock & Going to Tech

Dean’s taught at the university for more than 50 years – but he’s been in Lubbock even longer, growing up in the Hub City and attending Lubbock High School.

Dean was born in St. Mary of the Plains Hospital on 19th Street, in a building that later became the Café J restaurant. He grew up at 2608 20th Street, right behind the hospital and a block from the Texas Tech campus.

The family doctors were Olan Key and Sam Arnett, who had started Plains Hospital and Clinic in 1937. Two years later they sold it to the Sisters of St. Joseph in Orange, Calif. for $57,901 so they could just focus on medicine.

“If we needed to go to the doctor we just walked across the alley,” he said.

Dean thought of going to college at Southern Methodist University in Dallas.

“My mother was not happy about that – she didn’t want me to go to a Methodist school,” said Dean.

He had a scholarship to play baseball at Texas Tech and a journalism scholarship from the Lubbock Avalanche-Journal.

Dean didn’t have a burning desire to get away from his hometown, so he became a Red Raider.

“I mean – I’m living at home, my tuition and fees are paid for – why not?” he said.

Dean played baseball for Beattie Feathers, who’d played pro football with Red Grange. He then played for legendary coach Berl Huffman his last couple of years at Texas Tech.

He graduated with a marketing degree from the Department of Business Administration and a journalism minor.